The rise of Ukip: A signal that politics and democracy need to change

Claudia Chwalisz, Populus

The success of the British UK Independence Party (Ukip) should be understood as a signal. Our democratic institutions and processes should partially change to accommodate increased demands for new ways of citizen participation. These demands are particularly widespread amongst the Ukip electorate.

Does Ukip make a real difference to British politics? Ukip can be classified as a populist party due to its constant anti-elite rhetoric and its tendency to make use of xenophobic and anti-Islamic arguments. Most famous is perhaps Nigel Farage’s statement that mass immigration was making parts of the country appear like „a foreign land“. Currently, Ukip has only one parliamentary seat. This is down to the United Kingdom’s (UK) first past the post system, where the candidate with the greatest number of votes in each constituency wins the seat, even if they only win with a quarter of the vote in some cases. In May 2015, the party won 12.6 per cent of the vote, up from 3.2 per cent at the previous general elections. It came second in 120 seats. If the UK had a proportional representation system, Ukip would have won over 80 seats and would be the third largest party right now.

Ukip’s greatest damage was in Labour´s heartlands in the Midlands and the north of England

But, despite its lack of electoral power, Ukip should not be ignored and the mainstream parties cannot be complacent. Ukip is still polling at around 12-17 per cent, where they have remained steady for about two years. Despite common perceptions that the rise of Ukip has eaten into the Conservative vote, it has equally hurt Labour. In the 2015 general election, Ukip’s greatest damage was in Labour´s heartlands in the Midlands and the north of England. The biggest share of Labour’s 2010 vote went to Ukip in these seats. This makes a difference as research shows that if Labour had kept even a small percentage of those voters who switched to Ukip, they would have won an additional 13 seats that they had lost to the Tories.

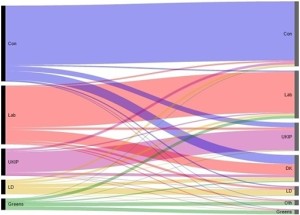

Recent YouGov polling also highlights that more people have left Labour and the Conservatives to switch to Ukip than the other way around (see figure below).

YouGov 2015, Voter flows since May 2015.

Ukip voters tend to be older, male, working class and less likely to have a university degree

It is why the academics Matthew Goodwin and Rob Ford categorise Ukip voters to some extent as the ‘left behind’ in Britain’s socioeconomic transformation, led by an out-of-touch elite. Ukip voters tend to be older, male, working class and less likely to have a university degree. This is a similar voter base to other right-wing populist parties in Europe, though in other countries there tends to be a coalition between the working class and the petite bourgeoisie that makes up the voter base.

Why has Ukip risen so suddenly in the past few years?

The Ukip vote is driven by four main factors:

1. An opposition to the EU

2. A dislike of immigration

3. A distrust of mainstream politicians from all political parties

4. A pessimism about the future

These four elements have become ever more important in British politics in recent years.

First, while the majority of the public does not list the EU amongst their top concerns, the fact that Cameron has promised a referendum on the issue was interpreted by some as a way of attempting to halt Ukip’s rise. It has clearly brought the issue to people’s minds and has created a pretty even split so far between the Leave and Remain camps. It remains to be seen whether the referendum campaign will help or hurt Ukip though. Eurosceptic donor money is going straight to the Leave campaigns rather than to the party. New research also shows that Nigel Farage is a damaging character to the Out campaigns – voters turn against ideas when they are associated with Farage and his party.

Ukip has tried to link the EU with the issue of immigration, which is really the party’s core concern

The other reason that the EU has become salient again is that Ukip has tried to link the EU with the issue of immigration, which is really the party’s core concern. Ukip wants Britain to ‘regain its sovereignty’ and control of its borders. It wants to put an end to free movement, which it only sees as a possibility if the UK leaves the EU. Ukip have tried to play up both economic and cultural arguments for why they think we have had too much immigration.

The third reason – distrust of mainstream politicians – is also significant. The social and economic shifts experienced over the past decades have hardened a deeply held scepticism about ‘the establishment’. In 1986, one in 10 Britons said they almost never trusted the government. In 2012, this rose to one in three. Research has shown that Ukip voters are driven by political disenchantment to the same extent as their opposition to immigration or the EU.

Finally, there are a number of reasons behind this democratic stress, linked to a pessimism about the future for a certain portion of the population. The development of the world economy has been a wonderful achievement, but not without challenges. The embrace of neo-liberalism in the 1980s and 90s created a divide between the so-called ‘winners’ and ‘losers’ of globalisation. There used to be a worker-owner divide in the UK; this was undermined with the decline of trade unions as the working class became more socially fragmented. All of this goes hand in hand with the downfall of collective organisations more generally and the rise of individualism. At the same time, inequality has been rising. Greater international mobility has been accompanied by a rise in multiculturalism. And a generational divide has grown.

The populist signal

Given the multitude of drivers behind the Ukip vote – economic, cultural, and political – there is clearly no single answer for defeating populism.

For some, looking to immigration as the source of society’s ills is merely a symptom of a greater malaise. Immigrants are the scapegoats; reducing immigration and coercing integration are the seemingly ‘easy’ answers to restricting societal change. Yet these demands skirt around the heart of the problem. Low growth, ageing populations, and rising levels of inequality have left Europeans in a state of uncertainty, concerned and disgruntled about their jobs, their pensions, their futures, and their children’s futures. Only an intricate mix of social policies and financial regulation could ensure solidarity and rebalance the power between the vast majority and the economic elites (i.e. housing and land policy, investment in skills and vocational training, raising the minimum wage, regulating corporate governance structures, etc.). Ukip, however, offers a ‘common sense’ and ‘simple’ solution that feeds off of the feeling of disillusionment.

There is a progressive patriotic narrative missing in Europe today

For others, immigration is more of a symbol of disrupted communities, undermined national identity, and a declining feeling of belonging than about economic fears per se. There is a progressive patriotic narrative missing in Europe today. Looking to Canada offers some inspiration. The new Liberal prime minister Justin Trudeau is making speeches to promote the idea that ‘diversity is our strength,’ and insisting that we cannot or should not judge people by their nationality or religion rather than by who they are as individuals, contributing to our shared society.

There are a multitude of drivers behind Ukip, but the political drivers are often overlooked. In my research published in The Populist Signal, I focus on the extent to which people’s feelings of disillusionment with politics has been fuelling support for populist parties in the UK specifically, and also in Europe more generally. The main argument is that demand for democratic change should not be ignored. Democracy is indeed more than just elections, and involving ordinary people in political decision-making draws on the inherent richness of diverse societies.

Demand for democratic change should not be ignored

In my research, I looked at ten case studies of what I called ‘democratic innovation’ from around the world, interviewing ministers, local politicians, campaigners, organisers, and also some ordinary people involved in these democratic experiments. Democratic innovations are a relatively new field of practice and research. The general idea is that our liberal democracies should open themselves up to new and semi-new ways of citizen participation in politics. After all, most of our current political institutions and processes date from the 19th century or even earlier. Democratic innovations include deliberative polling, town hall meetings, participatory budgeting, e-democracy, and many more approaches and combinations of approaches (a good overview can be found in this seminal book by Graham Smith). Most of the case studies I surveyed are in the form of citizens’ assemblies or citizens’ juries. The vast majority involved three things: the drawing of lots of participants to achieve diversity and representativeness, a focus on deliberation, and a chance to have real power or a genuine voice. These were not merely consultations, in which some sort of ‘engagement’ box could be ticked and in which any recommendations could be ignored.

An important example would be the Melbourne People’s Panel, organised and facilitated by the independent non-partisan newDemocracy Foundation, and held by the city council last year. A group of 43 randomly selected people from the city, representing both business and residents, came together over four months to deliberate and propose a 10 year, $5 billion AUD financial plan for the city to the Council. After reviewing their proposals, the councillors accepted roughly 90 per cent of the suggestions, implementing some more radical policies than they were intending to otherwise, especially when it came to environmental standards.

90 per cent of populist and outsider party voters would be willing to participate in a citizens’ assembly

The research is also based on polling (Ipsos MORI), asking people in the UK if they would be willing to participate in a randomly selected citizens’ assembly, either at the local level or the national level (on issues such as immigration, health education, etc.). The majority of people were willing, especially populist and outsider party voters, where support even went up to 90 per cent.

There is an assumption that most people just want politics to function well, but do not really want anything to do with it themselves. My research highlights that actually people care quite a lot about the process as well. And even populist voters, who we assume are voting out of protest and grievance, if given the opportunity to have a more active and deliberative form of political participation as an outlet for their concerns, would be willing to take it.

To conclude, these kinds of processes, where citizens are involved in public decision-making on a regular basis, and are given a genuine voice, could go a long way to helping increase trust in democracy and alleviate the underlying drivers of populism over the long term.

Claudia Chwalisz is a Consultant at Populus and a Crook Public Service Fellow at the Crick Centre, University of Sheffield.